Stylized version of the mythic Tena and Fura cliffs, the symbolic guardians of the emerald region in western Boyacá. As legend has it, Fura’s tears turned into emeralds deep inside the mountain. (Original image is courtesy of Dawn Jehle, adornate.co.uk). Tear-shaped emerald drops by Lalta NYC. (Photo: Lalta NYC). Evoking the region’s famed blue Morpho butterflies, this bejeweled brooch, with antennas en tremblant, is made in titanium, sapphires and diamonds, by Ioannis Alexandris. (Photo: Ioannis Alexandris)

Revisiting Colombia's emerald mines

Having visited several of the major emerald mines in Colombia a few years ago, I was delighted to have been invited back recently to see new mines and revisit others. This time my visit was to three distinctly different operations in terms of size, age and their "green" evolution.

By Cynthia Unninayar

By Cynthia Unninayar

|

It is no secret that emeralds from Colombia are considered to be the finest and most coveted in the world, but it is also no secret that, in the past, the nation’s industry was plagued by violence and rivalries. Happily, these problems are now but a distant memory and today the sector is thriving. And importantly, the emeralds produced in Colombia are “greener” than ever.

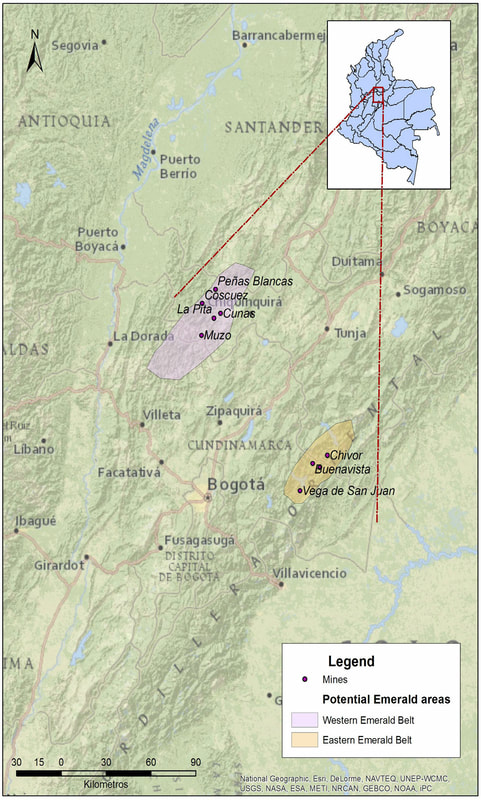

Over the last decade, the Colombian government has joined with the emerald industry to improve the sector and ensure best practices, including sustainability, transparency and corporate social responsibility (CSR), all while helping meet the needs of small-scale miners. It also encourages foreign investors who bring state-of-the-art technology and financing for large-scale gemstone mining in the region, and who can help improve the daily community life in the mining regions. Geologically Speaking Colombia’s emerald deposits are found in the Department of Boyacá, located in the Andean region in the Cordillera Oriental mountain range in central Colombia. The emeralds are distributed along both borders (eastern and western) of the Eastern Cordillera sedimentary basin, and the gems from the two areas exhibit different types of mineralization, due to their formation during different periods in geological history. Emeralds in the eastern side were created around 65 million years ago, while deposits in the western basin are younger, with ages around 38 to 32 million years ago. The western side includes the world-famous mining districts of Muzo, Coscuez, La Pita, Cunas and Peñas Blancas, among others. The eastern side includes the older deposits of Chivor, Gachalá and Macanal. Found in heavily faulted and folded sedimentary layers of mostly black shale, the green gems crystallize in a hexagonal pattern and owe their color to the presence of chromium and vanadium. Legends and More Many gemstones come steeped in legends, folklore and intrigue, and Colombian emeralds are no exception. One of these legends reveals the tale of “Fura” and “Tena,” two humans who were created by the god “Are” to populate the Earth. Are specified that the couple had to remain faithful to each other in order to retain eternal youth. Alas, Fura disobeyed and their immortality was taken away. When they eventually died, Are took pity on them and turned them into two cliffs protected from storms and serpents. Inside their great depths, Fura wept, and her remorseful tears turned into beautiful emeralds. Today, the Fura and Tena cliffs are the symbolic guardians of Colombia’s emerald zone, and rise 840 meters and 500 meters, respectively, above the Rio Minero valley. They are not far from the iconic Muzo and Coscuez mines. |

Reviving the Iconic Coscuez Mine

Starting our mine visit in Bogotá, before even the dawn had cracked over Colombia’s capital city, I was among five other intrepid adventurers who set out on the five-hour trip to visit the iconic Coscuez Mine.

The first couple of hours were on highways, but when we entered the mining region in Boyacá, travel slowed to a snail’s pace. Our drivers skillfully maneuvered our 4x4s as they jostled over narrow bumpy dirt roads that zigzagged through the incredibly lush verdant jungle. As we travelled through the luxurious rainforest, it was like a scene out of the movie Avatar.

Coscuez is one of Colombia’s most iconic mines and has produced some of the world’s finest emeralds since its discovery in 1646. Over the centuries, it was mined in the traditional manner with no investment in geology, technology or infrastructure. The main tunnel ran along a slope from 896 meters at the La Paz entrance up to 1251 meters at its Sabore entrance. About 80% of the secondary tunnels in Coscuez have been closed or are inaccessible because of very high inside temperatures or other unsafe conditions.

In January 2018, the newly created company, Fura Gems—named after the famous cliff—purchased 76% of Esmeracol, the previous owner of the Coscuez mine and holder of the Coscuez mining license that covers 0.47 square kilometers. Under the leadership of CEO Dev Shetty, Fura approached this new acquisition in a very scientific manner by making geological surveys and mapping existing tunnels.

Starting our mine visit in Bogotá, before even the dawn had cracked over Colombia’s capital city, I was among five other intrepid adventurers who set out on the five-hour trip to visit the iconic Coscuez Mine.

The first couple of hours were on highways, but when we entered the mining region in Boyacá, travel slowed to a snail’s pace. Our drivers skillfully maneuvered our 4x4s as they jostled over narrow bumpy dirt roads that zigzagged through the incredibly lush verdant jungle. As we travelled through the luxurious rainforest, it was like a scene out of the movie Avatar.

Coscuez is one of Colombia’s most iconic mines and has produced some of the world’s finest emeralds since its discovery in 1646. Over the centuries, it was mined in the traditional manner with no investment in geology, technology or infrastructure. The main tunnel ran along a slope from 896 meters at the La Paz entrance up to 1251 meters at its Sabore entrance. About 80% of the secondary tunnels in Coscuez have been closed or are inaccessible because of very high inside temperatures or other unsafe conditions.

In January 2018, the newly created company, Fura Gems—named after the famous cliff—purchased 76% of Esmeracol, the previous owner of the Coscuez mine and holder of the Coscuez mining license that covers 0.47 square kilometers. Under the leadership of CEO Dev Shetty, Fura approached this new acquisition in a very scientific manner by making geological surveys and mapping existing tunnels.

|

|

In March 2018, Fura Gems began a bulk sampling stage, digging 25 kilometers of tunnels through 10,000 tons of rock. Two months later, it discovered an exceptional 25.97-carat gem, which it dubbed the “Are Emerald,” after the mythological god in the Fura and Tena legend.

Technical innovation and scientific understanding are only part of Fura Gems' approach. The company has also made major changes in the way the mine interacts with the local community. “We aim to set a new precedent for best practices in the gemstone industry,” explained Shetty, “by transforming current standards into the premiere example of an enterprise that is employee-friendly, sustainability-driven and community-centered.”

“In the 10 months since our acquisition of the Coscuez Mine, we have hired 270 local miners and committed to working with 70 local suppliers,” added Rosey Perkins, manager of new projects and communication. Among its community-oriented non-mine activities is support for a health clinic, bakery, sewing center, carpentry workshop and English lessons. And, because removing mine waste in a green environmentally friendly manner is important, Fura created a special washing plant that is run by women.

“We have received more than 95% positive feedback from the local population about our activities,” said Maria Angelica Castilla, head of Sustainability, adding that Fura’s all-inclusive approach relies upon good communication with the local residents and aligns with other emerald producers in the region that are also raising operational standards and prioritizing community development.

The Fura team clearly wants to restore Coscuez to its former glory, while being a “green” operation and a real partner with the community.

Searching for Green at the Green Power Mine

The next morning, up again before the light of dawn, we headed to the Green Power Mine in the Muzo district. As the crow flies, the distances are not that great, but over the narrow mountainous roads, it took several hours. We drove first to the town of Muzo, where Julio Lopez, manager and part owner of the Green Power Mine, met us. We transferred to his vehicles and drivers for the rest of the journey.

Before long, we came to the banks of the Rio Minero, the main river flowing through the area. Here, dozens of “guaqueros” (independent surface miners) were looking for emeralds that may have washed down into the river from the mountains or from mining operations. Lopez explained that, with industrial mining now largely underground—instead of previous examples of razing entire mountains—the amount of emeralds in the river has declined dramatically, thus affecting the livelihoods of these “guaqueros.”

As we climb further into the mountains, we have a view of the distant Green Power mining camp and the entrance to the mine that is a few hundred meters below the buildings.

A newly established mine, Green Power was created by a group of individuals who came together to invest and explore for emeralds in this part of the Muzo district. They based their decision on geological surveys, which indicated good potential for the green gems in the area.

Technical innovation and scientific understanding are only part of Fura Gems' approach. The company has also made major changes in the way the mine interacts with the local community. “We aim to set a new precedent for best practices in the gemstone industry,” explained Shetty, “by transforming current standards into the premiere example of an enterprise that is employee-friendly, sustainability-driven and community-centered.”

“In the 10 months since our acquisition of the Coscuez Mine, we have hired 270 local miners and committed to working with 70 local suppliers,” added Rosey Perkins, manager of new projects and communication. Among its community-oriented non-mine activities is support for a health clinic, bakery, sewing center, carpentry workshop and English lessons. And, because removing mine waste in a green environmentally friendly manner is important, Fura created a special washing plant that is run by women.

“We have received more than 95% positive feedback from the local population about our activities,” said Maria Angelica Castilla, head of Sustainability, adding that Fura’s all-inclusive approach relies upon good communication with the local residents and aligns with other emerald producers in the region that are also raising operational standards and prioritizing community development.

The Fura team clearly wants to restore Coscuez to its former glory, while being a “green” operation and a real partner with the community.

Searching for Green at the Green Power Mine

The next morning, up again before the light of dawn, we headed to the Green Power Mine in the Muzo district. As the crow flies, the distances are not that great, but over the narrow mountainous roads, it took several hours. We drove first to the town of Muzo, where Julio Lopez, manager and part owner of the Green Power Mine, met us. We transferred to his vehicles and drivers for the rest of the journey.

Before long, we came to the banks of the Rio Minero, the main river flowing through the area. Here, dozens of “guaqueros” (independent surface miners) were looking for emeralds that may have washed down into the river from the mountains or from mining operations. Lopez explained that, with industrial mining now largely underground—instead of previous examples of razing entire mountains—the amount of emeralds in the river has declined dramatically, thus affecting the livelihoods of these “guaqueros.”

As we climb further into the mountains, we have a view of the distant Green Power mining camp and the entrance to the mine that is a few hundred meters below the buildings.

A newly established mine, Green Power was created by a group of individuals who came together to invest and explore for emeralds in this part of the Muzo district. They based their decision on geological surveys, which indicated good potential for the green gems in the area.

The first two years were spent building the installations and tunnels, and the mine became operational about 18 months ago. So far, the miners have tunneled more than 220 meters into the mountain, but have not yet found the green gems. Geological reports indicate that emeralds should occur in pockets at around 250 meters inside the mountain.

A small-scale mine, it has nine employees who work from 07h00 to 12h00 and from 13h00 to 17h00. They are all housed at the mine in a dormitory-styled setting, are provided meals and taken into town on their days off.

After lunch with the miners, our small group walks down to the mine’s entrance and puts on our headlamps. Stepping into the narrow tunnel, we were met with several centimeters of water covering the ground. In nearly all mines in the area, water is a continuous and often serious problem because the rains drain through the mountains and accumulate in the tunnels. This also makes the black shale walls wet and powdery. Merely touching them left thick black powder on our gloves.

At the tunnel’s end, we met the miners who were using jackhammers and explosives to continue lengthening the tunnel in their quest for the green gems. Even some members of our group tried their hand at maneuvering the heavy jackhammers to blast into the tunnel wall. As our group left, I asked Julio Lopez to let me know when they do strike emeralds, which should be soon.

A small-scale mine, it has nine employees who work from 07h00 to 12h00 and from 13h00 to 17h00. They are all housed at the mine in a dormitory-styled setting, are provided meals and taken into town on their days off.

After lunch with the miners, our small group walks down to the mine’s entrance and puts on our headlamps. Stepping into the narrow tunnel, we were met with several centimeters of water covering the ground. In nearly all mines in the area, water is a continuous and often serious problem because the rains drain through the mountains and accumulate in the tunnels. This also makes the black shale walls wet and powdery. Merely touching them left thick black powder on our gloves.

At the tunnel’s end, we met the miners who were using jackhammers and explosives to continue lengthening the tunnel in their quest for the green gems. Even some members of our group tried their hand at maneuvering the heavy jackhammers to blast into the tunnel wall. As our group left, I asked Julio Lopez to let me know when they do strike emeralds, which should be soon.

Revisiting Cunas

Our final destination on this mine visit was the high-producing Cunas Mine, owned by Esmeraldas Santa Rosa. This was my second trip to Cunas, having visited it in 2015 after the First World Emerald Symposium. Employing about 140 workers, Cunas is one of the largest mines in the area. At any one time, there are 70 miners who work shifts from 06h00 to 14h00 or from 14h00 to 22h00. There is also a small staff that manages life at the camp, including the meals and accommodations.

Because safety is a priority, a security team spends the night, after the last shift, walking through the tunnels, inspecting them for water and oxygen levels. Water is a serious issue at Cunas, and pumps continually remove water from the tunnels. Each miner also must carry a portable compressed air tank, which provides air for 40 to 90 minutes in case of emergency.

The employees all work 20 days continuously, and then have 10 days off. We spoke with two young women, both single mothers, who work at the mine’s small store for 20 days and then return home for 10 days to see their children, often cared for by a grandmother or other relative. While certainly not an ideal situation for these young ladies, they both declared that they were lucky to have the employment. Clearly, life in the mining areas is not easy, due to the remoteness of the emerald deposits, yet the large mines like Cunas and Coscuez provide gainful employment to the local communities where little existed before.

To enter the main tunnel at Cunas, we descend a long staircase, which ends in an 800-metre tunnel covered with several inches of water. Ventilation tubes run the entire length and pumps keep the water from flooding the tunnel. At the end, a large circular shaft houses a “lift” that takes miners and ore carts up and down to other levels. At the active face, miners carefully chisel out the emeralds from the tunnel walls. The precious gems are then placed in a pouch and taken to the surface.

Like other mines in the area, Esmeraldas Santa Rosa also takes corporate social responsibility seriously. Its social management plan is developed in three thematic areas: helping young people to continue studies in higher education; building lasting relationships with suppliers and distributors based on shared values; creating alliances with local populations for sustainable social development.

Our final destination on this mine visit was the high-producing Cunas Mine, owned by Esmeraldas Santa Rosa. This was my second trip to Cunas, having visited it in 2015 after the First World Emerald Symposium. Employing about 140 workers, Cunas is one of the largest mines in the area. At any one time, there are 70 miners who work shifts from 06h00 to 14h00 or from 14h00 to 22h00. There is also a small staff that manages life at the camp, including the meals and accommodations.

Because safety is a priority, a security team spends the night, after the last shift, walking through the tunnels, inspecting them for water and oxygen levels. Water is a serious issue at Cunas, and pumps continually remove water from the tunnels. Each miner also must carry a portable compressed air tank, which provides air for 40 to 90 minutes in case of emergency.

The employees all work 20 days continuously, and then have 10 days off. We spoke with two young women, both single mothers, who work at the mine’s small store for 20 days and then return home for 10 days to see their children, often cared for by a grandmother or other relative. While certainly not an ideal situation for these young ladies, they both declared that they were lucky to have the employment. Clearly, life in the mining areas is not easy, due to the remoteness of the emerald deposits, yet the large mines like Cunas and Coscuez provide gainful employment to the local communities where little existed before.

To enter the main tunnel at Cunas, we descend a long staircase, which ends in an 800-metre tunnel covered with several inches of water. Ventilation tubes run the entire length and pumps keep the water from flooding the tunnel. At the end, a large circular shaft houses a “lift” that takes miners and ore carts up and down to other levels. At the active face, miners carefully chisel out the emeralds from the tunnel walls. The precious gems are then placed in a pouch and taken to the surface.

Like other mines in the area, Esmeraldas Santa Rosa also takes corporate social responsibility seriously. Its social management plan is developed in three thematic areas: helping young people to continue studies in higher education; building lasting relationships with suppliers and distributors based on shared values; creating alliances with local populations for sustainable social development.

Sense of Camaraderie

As we prepared to leave the Cunas camp in the late afternoon, the skies darkened and a storm approached. Rain began to fall in sheets. Nonetheless, wanting to keep to our schedule, we started off. Alas, hardly a few kilometers later, we could go no farther. The powerful rains had caused a landslide and the narrow road was blocked. Water fell over the side of the mountain like a waterfall. We had no choice but to return to the camp.

In a show of solidarity and kindness, the manager of the camp, Bryan Martinez, arranged to give us dinner, and then shuffled people around in the miners’ quarters so that we could have a bed for the night. He told us that he would have the road cleared in the morning after the storm had passed. We were all touched by the camaraderie, support and good wishes of everyone at the camp.

Following breakfast and thankful goodbyes to the camp personnel, we continued our journey, leaving the mine country for a cultural pause in the delightful 16th century town of Villa de Leyva.

As we prepared to leave the Cunas camp in the late afternoon, the skies darkened and a storm approached. Rain began to fall in sheets. Nonetheless, wanting to keep to our schedule, we started off. Alas, hardly a few kilometers later, we could go no farther. The powerful rains had caused a landslide and the narrow road was blocked. Water fell over the side of the mountain like a waterfall. We had no choice but to return to the camp.

In a show of solidarity and kindness, the manager of the camp, Bryan Martinez, arranged to give us dinner, and then shuffled people around in the miners’ quarters so that we could have a bed for the night. He told us that he would have the road cleared in the morning after the storm had passed. We were all touched by the camaraderie, support and good wishes of everyone at the camp.

Following breakfast and thankful goodbyes to the camp personnel, we continued our journey, leaving the mine country for a cultural pause in the delightful 16th century town of Villa de Leyva.

When literally stranded in the jungle during a severe storm that caused a landslide blocking the road out of the area, the manager of the Cunas Mine welcomed our group back to the camp to spend the night. The next morning, his crew cleared the road so we could continue back to Bogotá. (Photo: Lalta Keswani)

Cultural Stopover

The colonial town of Villa de Leyva was founded in 1572 by the first president of the New Kingdom of Granada, Andrés Díaz Venero de Leyva. Situated in a high-altitude valley of semi-desert terrain, with no apparent nearby mineral deposits, and far from major trade routes, Villa de Leyva has not changed much in the last 445+ years.

As a result, it has preserved its original colonial style and architecture, with many buildings dating to the 16th century. The 14,000-square-meter cobblestone central plaza is the largest square in Colombia and perhaps in South America. One of the nation’s main tourist attractions, it was declared a National Monument in 1954.

The small town is also one of the few anywhere to boast three paleontological museums. The valley is rich in fossils from the Paja Formation during the Cretaceous era (some 120 million years ago) and the museums abound with remarkable specimens. Probably the most spectacular is the fossil of a Kronosaurus boyacensis, an extinct genus of large marine reptiles. Discovered in 1977 by farmers in the area, the Kronosaurus was left in place and a building constructed around it. Measuring nearly 30 feet in length, it shares the museum with other remarkable fossils.

After a delightful brief night’s stay in Villa de Leyva, we returned to Bogotá, with fond memories of the warm hospitality we received at the mines where emeralds are definitely “green.”

(All photos by Cynthia Unninayar, unless otherwise specified.)

The colonial town of Villa de Leyva was founded in 1572 by the first president of the New Kingdom of Granada, Andrés Díaz Venero de Leyva. Situated in a high-altitude valley of semi-desert terrain, with no apparent nearby mineral deposits, and far from major trade routes, Villa de Leyva has not changed much in the last 445+ years.

As a result, it has preserved its original colonial style and architecture, with many buildings dating to the 16th century. The 14,000-square-meter cobblestone central plaza is the largest square in Colombia and perhaps in South America. One of the nation’s main tourist attractions, it was declared a National Monument in 1954.

The small town is also one of the few anywhere to boast three paleontological museums. The valley is rich in fossils from the Paja Formation during the Cretaceous era (some 120 million years ago) and the museums abound with remarkable specimens. Probably the most spectacular is the fossil of a Kronosaurus boyacensis, an extinct genus of large marine reptiles. Discovered in 1977 by farmers in the area, the Kronosaurus was left in place and a building constructed around it. Measuring nearly 30 feet in length, it shares the museum with other remarkable fossils.

After a delightful brief night’s stay in Villa de Leyva, we returned to Bogotá, with fond memories of the warm hospitality we received at the mines where emeralds are definitely “green.”

(All photos by Cynthia Unninayar, unless otherwise specified.)